If we had records of massacres as we have meteorological records, don’t you think we might discover their internal laws, after several centuries of observation? — Joseph de Maistre.

There hasn’t been a world war in sixty years. There have been skirmishes, of course, but even in these, the chance that a soldier dies fighting has been on the decline. Nor have we had a really juicy atrocity these many years. Oh, sure, there have been divers bombings and the odd plane flying into a building, but no Great Leaps Forward or Cultural Revolutions.

Fewer people are turning up dead by the hand of another. It’s hard to buy a slave for the love of money. Courts have given up torture and more countries are following the lead of those most enlightened fellows, the Europeans, and won’t condemn even the most vicious beast to death.

You can’t openly spank your kid in England. Homosexuals are now mostly treated like One Of Us. Rape, lynchings, and other malfeasances to the body are way down over the past century. The Black and the White are now, if not brothers, then at least kissing cousins. And let’s don’t forget that fewer hunters are taking to the woods to kill and gut Bambi.

Heck, more and more people won’t even eat the meat the hunter brings back. And, and long last, thanks to Blue State Benevolence, there comes the recognition of the sentience of chickens.

Sentient chickens?

Yes, you read that right. It is thinker Steven Pinker’s contention that chickens are on par, brain wise, with people. So concerned about our feathered friends is he, that he frets that our now more healthy “lifestyles” which insist upon white, not dark, meat, “creates the demand for a vastly larger number of sentient lives to be brought into being and snuffed out to meet the same demand.”

Our man is also responsible for the other suppositions given above. He provides statistical charts as evidence that violence qua violence has been decreasing, not just over decades, but through time in general. If true, the questions is why?

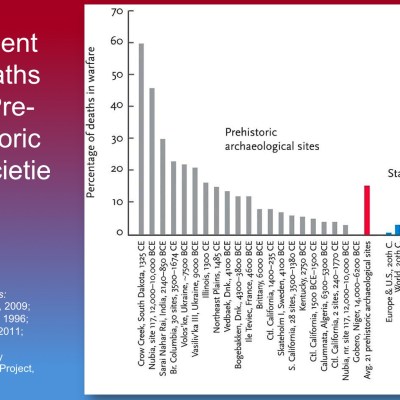

Pinker has answers, but before those, it’s first crucial to understand his evidence. Unfortunately, his charts are muddled and even misleading. Take one which shows, via archaeological digs, a crude guess of the percentage of deaths in warfare in prehistoric societies. It appears that death rates dropped from 60% down to a paltry 1 to 3% for 20th century humans.

But that decrease is largely apparent, because the times of the digs are not presented linearly. The graph begins with the Crow Creek tribe of (what is now) South Dakota. In the year 1325—not that long ago, relatively speaking—the death rate of Crows knocking each other on the heads was near 60%. But in 12,000 to 10,000 BC, Nubians going to battle would die at the same rate as would soldiers in World War II. A reordering of this chart by date merely shows that death rate varies, but is not necessarily decreasing.

He repeats the error in his second chart, comparing death rates in non-state versus state-run societies. A close look shows that many non-states had the same, or even lower, death rates than modern states. And this must necessarily be so because, of course, the modern state is only a couple of hundred years old. That is, there must be many more data points of non-state societies than of state-run societies. What, therefore, is of more interest is why have states developed? Pinker doesn’t answer.

It’s also so, as his statistics show, that major wars between super powers have become rare. Too, death rates of soldiers in modern wars are decreasing. But proxy wars have not diminished much in frequency. Nor does he proffer the most likely explanation why fewer soldiers are dying. Of that, more in a moment.

Homicides in England, elsewhere in Europe, and certainly in the United States, have been declining. Pinker shows data from about 1500 AD, which of course is a vastly shorter time span than the military death rates. He is on stronger ground here: these drops in murders are probably real.

But what about the abolition of judicial torture? Pinker shows a picture implying it’s on the way out. It may be that torture is officially off the book; it certainly isn’t used routinely as it once was. In China, for example, all suspects were routinely beaten as they came before the magistrate. Not because the magistrates were seeking information the prisoners were reluctant to provide, but merely to put the possible criminals in the proper frame of mind. After the beatings, then the questioning (with more beatings) would begin. Torture, however, hasn’t been abandoned even in modern states, though it now, to soften the blow, is spoken of only in euphemism.

Slavery, as Pinker’s chart shows, has been decreasing radically since the late eighteenth century. And his many other charts showing toleration of homosexuals, increasing in vegetarianism, decline in death penalty use, are all largely accurate. But they are all of widely different scales, and unless one is not careful, it’s possible to believe that all these things are declining at the same rate.

Why?

If humans are dying less often in war, why? Pinker never mentions nor ever credits the two most likely explanations for this, and his other, displays. One: human population has been exponentially increasing. Two: that increase was (almost wholly) possible because of the increase in knowledge, gadgets, and guns.

Shoot a solider today and it’s likely that he’ll be evacuated forthwith, operated on within minutes, so that he’ll probably survive. But wander onto the Great Plains a millennium ago, and odds were even a simple cut would turn septic and kill.

Most soldiers now will not fire a weapon in anger. Many are posed behind computers far from danger. Even a century ago, all fought, with generals leading the charge and no sitting it out in a bunker.

Why haven’t Russia or Red China launched their missiles at us or their neighbors? Conventional thinking says the engines of war are now so frightening that the super powers do not want to risk retaliation and possible destruction. This is why there has been an increase in proxy wars. But Pinker believes, for example, that nuclear weapons are “militarily useless…The theory of the Nuclear Peace is quite popular, but I’m skeptical.” Military useless? That opinion has been expressed, but only by a minority of generals.

And Pinker has forgotten—a major flaw—chemical and germ warfare. People were so horrified by their use in World War I, that no large state dared try them again. But several small countries did, most notably Saddam Hussein and his slaughter of the Kurds. Iran still threatens their use.

Pinker, a Blue member of a Blue State, credits the Enlightenment and, well, people like himself for the softening of human attitudes:

With a lot of these statistics, the red states today have attitudes that the blue states had 30 years ago—toward women, towards spanking, towards homosexuals, towards animal rights, and so on…[Y]ou can see a continuum in the world in a lot of variables related to the decline of violence: Western Europe, then the American blue states, then the American red states, then Latin America and Asian democracies, and the Islamic world and Africa pulling up the rear.

There is something to this. People the world over, in places like Greece, Spain, and now Wall Street, regularly march, shout, and destroy property to show how dissatisfied they are with the idea of violence. But are these attitudes instilled by Seeing the Secular Light or because, with the increase in knowledge, people have it better? Raids and skirmishes are not seen as important as downloading the newest app on your iPad.

Pinker considers this, but dismisses the idea as a main force. But isn’t it a more likely explanation to say that slavery became rare because, with the introduction of the internal combustion engine and so forth, it was no longer necessary, rather than because people began to feel an internal glow from their powers of thought? About the amazing properties of the Enlightenment, even Voltaire said, “Le raisonner tristement s’accédite.”

A popular bit of psychology has it that people kill because they either “dehumanize” or “demonize” their victims. It’s science: “Daniel Goldhagen has set up a 2 X 2 taxonomy of genocides according to whether the victims were demonized, de-humanized, or both.” While this might happen in some instances, it is false in general—although that word demonize is sufficiently malleable to apply to any situation where two or more powers go to war. Who, after all, fights a beloved enemy? Take those plains Indians raiding each other’s camps: they depended on their enemy’s humanness; indeed, their honor, the main reason they fought, depended on it.

He finally comes to Hobbes, and his theory that

Leviathan, namely a state and justice system with a monopoly on legitimate use of violence, can reduce aggregate violence by eliminating the incentives for exploitative attack; by reducing the need for deterrence and vengeance (because Leviathan is going to deter your enemies so you don’t have to), and by circumventing self-serving biases.

Locke thought the same, and so did John Adams, etc. This explanation has a lot more going for it, but Pinker has forgotten the cautions of Robert Nisbet, who warned that as the State abrogated its right to mete out justice, the people would take it back upon themselves. If a large number of folk think that criminals are “getting away with it”, we should see an increase in vigilantism and honor killings. And of those, the evidence is increasing.

Pinker mentions an increase in knowledge tangentially, by saying what is uncontroversial: trade decreases the probability of belligerence, all other things equal. But they are hardly ever are equal, or they are not for long.

The final force which has neutered our violent tendencies is “what Peter Singer called the ‘Expanding Circle’.”

According to this theory, evolution bequeathed us with a sense of empathy. That’s the good news; the bad news is that by default, we apply it only to a narrow circle of allies and family. But over history, one can see the circle of empathy expanding: from the village to the clan to the tribe to the nation to more recently to other races, both sexes, children, and even other species.

However—and Pinker recognizes this to some extent—this is a not a theory for why violence has been decreasing, it merely calls the decrease by another name.

Surprisingly, Pinker gives his theories before a group of evolutionary psychologists who do not press him on the major flaw in his reasoning. If human behavior has fundamentally changed, it must be because humans themselves have changed biologically. Have we evolved out of meanness?

The only theory of major human evolution I know of is Julian Jaynes’s abrupt origin of unicameral mind. Pre-modern humans had brains that were two,bicameral, a biological quirk that allowed them to communicate with the Gods. But, and not that long ago, a mutation occurred which make brain as one, enabling us to think our way out of tough situations.

It’s important to consider these things, because decreasing violence is something to be encouraged. If it takes “circles of empathy” to quell murderousness, then by golly, let’s circle them empathies. If Enlightenment and secularism really can pacify and sooth the soul of the savage beast, then snap on the lights and ban religion. It’ll be worth the occasional mass starvation, bloody spree, or gulag archipelago to ensure Utopia.

You seem to have Julian Jaynes’s theory backwards. Bicameral comes first and then the modern switch to the unicameral. He relates it to schizophrenia and it is a very odd theory.

I am not sure that you need a full genetic shift to explain a reduction in violence. A culling of the most violent through execution or jail may remove them from the breeding population in every generation, but not prevent a relapse to the feral condition when state sanction is removed during a breakdown of government. That is, we are domesticated.

All,

The main text passed without comment other of Pinker’s figures. I do not want this silence to be taken for consent. For example, the in the atrocities plot, prepared by a pal of his, we see WWI and WWII aren’t even in the top 10. And I don’t place Mao’s fantasies. The problem is that this graph uses as a denominator world population. Generally, I like this trend: too often the population change in neglected. But if you were a Chinese professor in 1967 and saw a mob of Little-Red-Book carrying fanatics chasing after you with knives, you might wonder if the denominator should have been China’s and not the world’s population. And if dividing by the world’s population was proper, then it should have been applied to the other graphs, which it was not.

Also under the heading of “Increased Knowledge” has been the increase in efficacy of police work, which prevents crime.

William Sears,

Yes! Stupid mistake on my part. I’ll fix.

The total number of deaths caused almost exclusively by political violence of secular states during the Twentieth Century is “somewhere around 180 millions”. Rummel claims 170 millions and that this is more than all of the atrocities in recorded history up to the end of the Nineteenth Century. Much to his annoyance, The Git cannot find the reference to the historical comparison. I did some research on this when Richard Dawkins was rabbiting on about most violent deaths being caused by religious fanaticism.

And The Git is reminded that many of our librarians here in Tasmania have been replaced by library technicians because they cost less. Grrrr! How the hell are we supposed to research without competent librarians? And why have they changed the perfectly understandable word “library” with the cryptic “LINC”?

Having kept animals for decades, I can tell you that goats, sheep, dogs etc all need the company of at least one other animal, or they fret. It is noticeable that they do not class chickens as fellow animals. The Git is not alone in noticing this. Is Pinker perhaps claiming that he has the brains of a chicken?

I tend to agree with Pinker’s general statement that per capita vilence and death have been heading downwards, but I think it a fool’s errand to relate declines in war-related death to declines in crime to declines in general attitudes. Combine them all in search of one Grand Unified Theory and you lose the ability to see the trees for the forest. And in teh end, the forest is composed of trees.

Just looking at war, the patterns of conflict have been so diverse across time and geography, throwing it all into one sieve and thensaying “here’s the answer” seems, well, childish. The Assyrians killed whole populations, teh Grreeks didn’t, the Romans tended not to unless they were really pissed but then they tended more toward enslavement or exile than genocide. Look at war as practiced by the Mongols, or the Thirty Years War, and contrast with the Hundred Years War, the Wars of Religion, the dynastic wars of Louis XIV-XV, the Napoleonic Wars, on and on… all over the place in terms of lethality, combat deaths versus soldier deaths from non-combat causes versus civilian deaths. Yes, probably an overall trend, but very situation-specific and driven by a whole lot of factors other than the general psycho-social things that Pinker sees based on his own background and speaking to a bunch of other cognitive scientists. I could make just as persuasive a case based on economics and military technology.

“Nor have we had a really juicy atrocity these many years.” -Rwanda forgotten already.

“chemical and germ warfare. People were so horrified by their use in World War I, that no large state dared try them again.” Didn’t Italy use poison gas in Ethiopia? Maybe the lesson is that no large state tried them again against enemies who might reply in kind.

P.S. I admit that I’m not sure whether it was “poison gas” in the modern sense or in the sense sometimes used in the 20s and 30s of what we’d call “tear gas”.

“Are Humans As Violent As In The Good Old Days?”

Yes, but now we are more polite and caring about it — if only in word. We do so like to pretend.

All,

Re: decreases in homicide. The blurb from A&LD, “The great illumination. Streetlights changed everything, a fact not lost on those who prefer the dark: thieves, prostitutes, drunks, students…more.”

Can’t we all stop arguing and just blame all this darned peace and prosperity on anthroprogenic global warming?

Why deny the science? More food = more plants = more people = more CO2 (but not necessarily in that order)

Yet another reason to fight AGW and return to simpler times, when killin’ n pilligin’ were done the old fashioned way.

This entry from Blute Blog

http://bluteblog.com/2010/12/08/gene-culture-coevolution-and-genomics/

particularly “Nervous system, brain function and development; language skills and vocal learning” lists genes identified as having been subject to recent rapid selection and their inferred cultural selection pressures.

“slavery, homosexuals, vegetarianism, etc.”

Why does Pinker identify his (chronologically) provincial biases with evolution in morality?

“Didn’t Italy use poison gas in Ethiopia?”

Yes.

And the deaths among Crow, Tasmanians, and the like have occurred because there are so few of them now. If there were 10 million Aztecs, I doubt Pinker’s random collection of facts would support his thesis.

Watching ants and flies attack my picnic lunch, I’ve come to the conclusion that the reduction in violence is an economic and life expectancy issue. Those ants and flies have very short life expectancies, so risking their lives for my salad and sandwiches is a pretty reasonable risk for them. Likewise, with life expectancies of 30 or 40 years, it was a pretty good risk for our ancestors to hazard an ocean voyage for a chance at homesteading a farm and having a large family.

For us, a small risk of a 1 or 2 percent chance of getting killed in an auto accident over a period of 70 or 80 years is worth the risk when the payoff is having a much larger opportunity to find a desirable mate and profitable career.

Putting those two together, it’s technology and an increased life expectancy that has made war a bad risk. The longer our life expectancy, the greater the potential loss from an early death in warfare. Give us humans a drastically reduced life expectancy due to drug immune superbugs or whatever, and warfare might well have a positive economic payoff again.

Pingback: Are Wars And Violence Decreasing? Taleb’s New Paper Reviewed | William M. Briggs